PART 1/2: First Nations Wholistic Policy and Planning Model

- samkriksic

- Jun 23, 2020

- 4 min read

Updated: Jul 25, 2020

Follow up post (Part 2/2) is available here: Upstream Currents - An Examination of Youth Nunavummiut Mental Health, utilizing the Wholistic Policy and Planning Model to examine this health issue.

Introduction

It is widely understood and accepted that the Nunavummiut and Inuit peoples of Canada face arguably greater health disparities than their southern neighbors (Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, 2014). Various factors contribute to the great disparities that exist, demonstrated through an examination of the Social Determinants of Health. Considering the southern regions in Canada pale in comparison to Nunavut’s overcrowded housing, high unemployment rates, low rates of secondary education, consistently high rates of food insecurity, and disproportionately higher rates of risk factors (i.e. smoking), we must ask ourselves how to effectively evaluate and act on these disparities beyond the micro individual level (Department of Health, 2016). The Assembly of First Nations (AFN) Wholistic and Policy Planning Model is one such multilevel, or upstream, method of addressing these concerns (AFN, 2013).

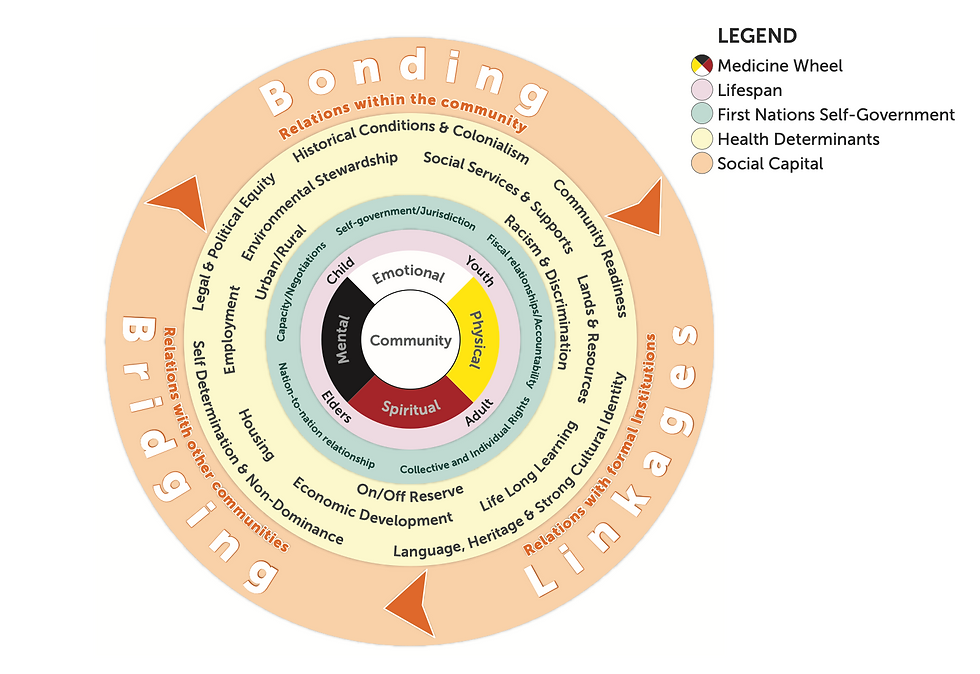

The Assembly of First Nations (AFN) Wholistic and Policy Planning Model is presented as a framework for informed policy development. It is meant to serve as a means to prompt upstream thinking, as opposed to the oppressive colonial behavior of defining the Inuit and First Nations communities as unhealthy, leading to further stigma, discrimination, and impeding self-determination (AFN, 2013). The model is inclusive of holistic Indigenous ideologies and is structured as a non-linear sphere, in which the dimensions are layered. The framework is comprised of key characteristics, which are summarized below.

The Community at the Core

First Nations and Inuit recognize the individual as greater than the self and more intrinsically related to community or family – part of a greater whole. As described in traditional Inuit knowledge, “all people have mind, body and spirit. The Inuit way of being is built on the relationships between these areas of the individuals life and the rest of the human and natural world” (Tagalik, 2012). The community at the core, in contrast to the individual at the core, represents First Nations and Inuit ideologies and values.

Components of the Medicine Wheel

Traditional First Nations and Inuit well-being are demonstrated through the Medicine Wheel, inclusive of 4 sections that create the wheel or whole person: physical, emotional, spiritual, and mental. The medicine wheel is a cultural health foundation “because in it resides the sense of identity, the collective social supports for the individual, and the sense of belonging grounded in loving, healthy and supportive relationships” (Tagalik, 2012).

Four Cycles of the Lifespan

Reading and Wien determined that “health is not only experienced across physical, spiritual, emotional and mental dimensions, but is also experienced over the life course” (Reading & Wien, 2009). They establish how determinants can have effects across multiple health stages and “may themselves create conditions (i.e. determinants) that subsequently influence health” (Reading & Wiens, 2009). It is imperative to include the dimension of lifespan within a First Nations or Inuit framework, as it accepts First Nations or Inuit traditional knowledge and practices as evolving. Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit is the term for traditional knowledge and is defined as “Inuit ways past, present and future” (Tagalik, 2012). In recognition of colonialism, these layer is imperative to address the intergenerational trauma that exists within Inuit and First Nations culture and demonstrates the cyclical nature of health disparity

Four Key Dimension of First Nations Self-Government

Embedded within this layer of the model are self-government/jurisdiction, fiscal relationships/accountability, collective and individual rights, nation-to-nation relationship, and capacity/negotiations. As per the Canadian Council on Social Determinants of health, this layer further adds to the holistic upstream approach to analysis and framework for Inuit health as it prompts consideration for socio-political or intersectoral factors, including historical and ongoing barriers to health (2015).

Social Determinants of Health

The subsequent layer within the framework is the social determinants of health or indicators of health, including self-determination, environmental stewardship, social services, justice, gender, life long learning, language, heritage, and culture, urban/rural, lands and resources, economic development, employment, health care, on/away from reserve, and housing (AFN, 2013). As per the Canadian Counsel on the Social Determinants of Health, these indicators can be considered “elements upon which upstream action can be taken” (2015). The framework is intended to be adaptable for use by a specific group, community, population, or health concern, making this model effective for both targeted initiatives or broad-spectrum analysis (AFN, 2013).

Three Components of Social Capital

The final layer of the framework is comprised of three concepts of social capital, which includes: bonding (relations with the community), bridging (relations with other communities), and linkage (relations with formal institutions) (AFN, 2013). This layer assists in demonstrating how intersectoral collaboration is imperative to ensure a holistic, First Nations or Inuit lens is utilized and is necessary to combat the historical social exclusion or colonial practices that have previously guided policy decisions as they relate to First Nations and Inuit health (AFN, 2013).

Conclusion

Health inequity has plagued First Nations and Inuit populations in Canada for generations, in its direct health effects within communities, but also in how we address it. Utilizing a First Nations or Inuit framework to address the needs or disparities within those populations will assist to decolonize the region and recognize the values and inherent priorities of these cultures. The Assembly of First Nations Wholistic Policy and Planning Model is overall adaptable and presents an intersectoral approach that addresses systemic issues of health. It is well designed to address issues related to colonialism and social exclusion and features important First Nations and Inuit traditional knowledge, making it inclusive with the promotion of self-governance.

References

Assembly of First Nations. (2013). First Nations wholistic policy and planning: A transitional discussion document on the social determinants of health. Retrieved from http://health.afn.ca/uploads/files/sdoh_afn.pdf

Canadian Council on Social Determinants of Health. Social Determinants of Health Framework Task Group, & Canadian Council on Social Determinants of Health. Social Determinants of Health Framework Task Group. (2015). A Review of Frameworks on the Determinants of Health. Ontario, Canada: Canadian Council on Social Determinants of Health. Retrieved from http://ccsdh.ca/images/uploads/Frameworks_Report_English.pdf

Department of Health. (2016, March). Health Profile Nunavut: Information to 2014. [Report]. Government of Nunavut. Retrieved from https://www.gov.nu.ca/sites/default/files/files/health_profile_nunavut.pdf

Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami. (2014, September). Comprehensive Report on the Social Determinants of Inuit Health. Retrieved June 11, 2020, from https://www.itk.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/ITK_Social_Determinants_Report.pdf

Reading, C. L., & Wien, F. (2009). Health inequalities and social determinants of Aboriginal peoples’ health. Prince George: National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health. Retrieved from https://www.nccah-ccnsa.ca/docs/social%20determinates/nccah-loppie-wien_report.pdf

Tagalik, S. (2012). Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit: The role of Indigenous knowledge in supporting wellness In Inuit communities in Nunavut. Retrieved from https://www.ccnsa-nccah.ca/docs/health/FS-InuitQaujimajatuqangitWellnessNunavut-Tagalik-EN.pdf

Comments