#MHST601 Finale: Refections on Remote Inuit Community Health

- samkriksic

- Aug 1, 2020

- 7 min read

(Image of Qikiqtani General Hospital, n.d.)

Introduction

Remote Inuit communities face distinctive and magnified health inequities less commonly seen in the southern regions of Canada. This can, in part, be attributed to the remote location, harsh environment, and lagging development of infrastructure. Remote Inuit health presents a unique and complex concern for the Canadian government and requires an equally unique, culturally competent approaches to combat the health disparities. Throughout this foundational course, it has been a privilege to try and better understand the health system of this distinct population. An emerging conclusion is that there is a continued need to focus on 1) identification and understanding of health in remote Canadian Inuit communities, and 2) a multilevel, collaborative approach to inform future action. It has been particularly educational to observe the potential for an amplified technological approach (eHealth/virtual care) to the betterment of health care in Nunavut, amid the Coronavirus pandemic. Having worked closely with this population, this course has helped to illuminate some of the systemic barriers that I may have otherwise been oblivious to.

Understanding

In order to address the distinctive health inequities experienced by remote Inuit communities, residents, practitioners, organizations, and governments must consider why they continue to occur and how this impacts health and disease management. The World Health Organization’s Social Determinants of Health are well-defined to identify health inequities, however, Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami’s (ITK, a national Inuit representation and advocacy group) Inuit Determinants of Health offer a culturally appropriate lens to amplify understanding of the specific context of life in remote Inuit communities (ITK, 2014). These determinants, or health vulnerabilities, are demonstrated through poor “health outcomes and experience of adverse social determinants of health” and can “be considered a product of both internal factors (e.g. limited capacity to consent) and external factors (e.g., subordinate position)” (Clark & Preto, 2018). An example of a negative outcome in health-related to a determinant experienced by remote Inuit communities is inadequate housing, which is linked to higher rates of respiratory disease, as demonstrated through Nunavut’s rates of Tuberculosis, which far surpass Canada’s national average (Patterson et al., 2018). Similarly, poor childhood development is linked to higher rates of mental illness (Kral et al., 2016). The Government of Nunavut (GN) published the 2014 Health Profile, underlining six key determinants for Nunavummiut health: education, housing, employment, risk factors, community strengths, and food insecurity (Department of Health, 2016). By acknowledging the fundamental distinction of the Inuit culture and remoteness of geographical location, the GN has established a culturally appropriate and effective means of addressing the determinants and health vulnerability, which have shaped health policy and initiatives in Nunavut in the recent years. The GN has announced various calls for proposals, including one for food security initiatives in 2019 (GN, 2019). Examples of current governmental actions include the Nunavut Suicide Prevention Strategy, Tobacco Reduction Framework for Action, and the Nunavut Food Security Strategy and Action Plan (Department of Health, 2020). Although this shows promise towards improving conditions in remote communities, there is further need for swift and sustainable action on a local, provincial, and federal level. Throughout this course, I have been able to reflect on the various means of identifying the determinants and linked the impact of these health vulnerabilities to disease prevention and management.

Building Capacity

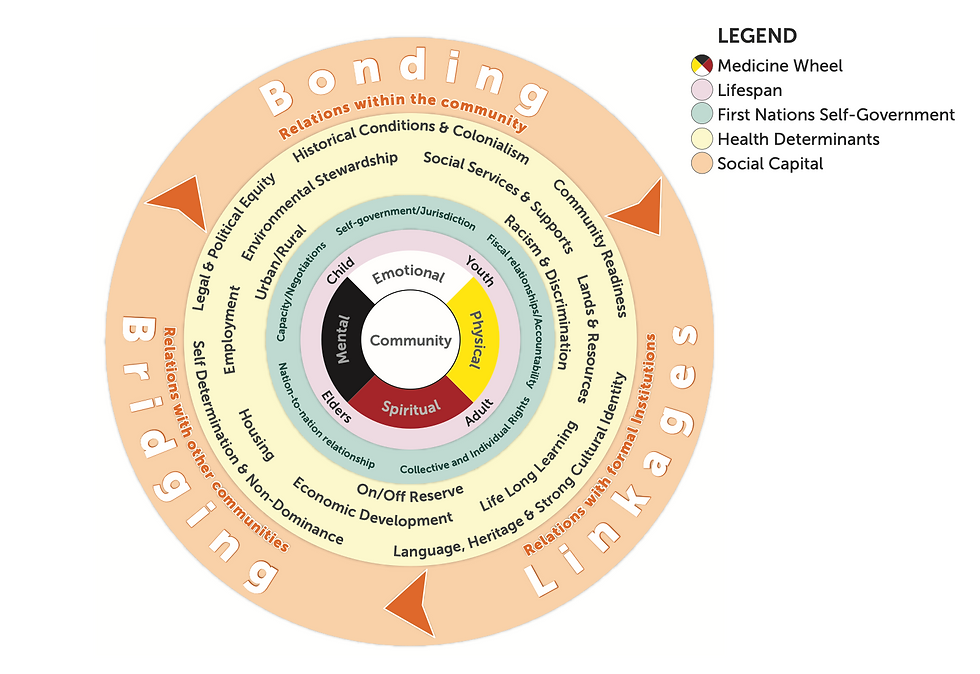

As remote communities continue to struggle with health inequities unique to the region, further collaboration is required within and beyond health systems, including community engagement, sustainable multidisciplinary teams, and governmental/organizational partnerships. Nunavut’s history is complicated by the rapid colonization of the territory. Future initiatives need to reflect Indigenous and Inuit health practices, which, “would allow the healing and wellness strengths of Inuit culture and society to flourish as integral parts of the health system” (Healey, 2017). Healey further highlights that recent efforts have been made for Inuit engagement, but that there is a need for health programming to be “born from Indigenous perspectives on wellness, from the design to the implementation and delivery” (2017). Incorporation of Indigenous and Inuit perspectives in health care will lead to a better understanding of the culture and priorities and allow for more effective systems to replace current westernized approaches. Additionally, utilization of interprofessional collaboration, inclusive of Inuit perspectives/practitioners, are required to address the health needs in remote communities. As Nunavut’s remote region has limited infrastructure and small populations, there is a shortage of qualified health professionals. Building multidisciplinary teams (inclusive of remote/virtual connections) with support from Inuit health practitioners in-territory can provide a more comprehensive and culturally appropriate approach to remote health care for this region. For example, the Arctic College offers programs such as the unregulated Social Service Worker Program, empowering Nunavummiut to access education and employment that is “strongly connected to Inuit Qaujimajatuqungit [Inuit epistemology],” which will, in turn, create culturally inclusive health teams and result in capacity building in the north (Arctic College, n.d.). Another way to address the health disparities experienced by Inuit in remote communities is to employ multilevel models of health that reflect Inuit and Indigenous perspectives. Models such as the Assembly of First Nations’ (AFN) Wholistic Policy and Planning Model address concerns unique to remote Indigenous communities and offer a culturally appropriate lens on health care for this population (AFN, 2013). This model applies an intersectoral approach, highlighting community participation, self-governance, and inter-governmental collaboration as a means of upstream policy development to support positives change in these communities (AFN, 2013). Built into this model is the need for multilevel governmental/organizational partnerships, which can be seen through the collaborative efforts of various Canadian provinces, including Ontario, to ensure Nunavummiut receive the required health care, which cannot be otherwise offered in-territory. Such partnerships need continued development and refinement, through the supportive guise of the Federal Government. In reflection of these topics over the past few weeks, I have gained the understanding that people and systems need to collaborate on Inuit health system goals to empower remote Inuit communities to build capacity in-territory. While offering cultural competence courses to Ontario practitioners is always welcome, future directions for Nunavut’s health system must be focused on identifying Nunavummiut priorities and goals and focus on enabling this population to develop the capacity to offer culturally appropriate care at home.

Trailblazing

Having reviewed the identification and understanding of health inequities in remote communities and examined the necessary collaboration and capacity building for culturally inclusive, multi-level teams and models, one can then begin to consider how Nunavut’s healthscape can progress. The greatest impact will manifest through the continued rise of eHealth and virtual care, and Nunavut is well-positioned to take the lead, having already commenced piloting such programs. There are infrastructure and cultural concerns currently limiting the use of said technologies, such as reliable broadband infrastructure and persistent language barriers; however, with continued investment and development and careful implementation, Nunavut can create a health care model that supports increased quality care in-territory, limiting the need for expensive and cumbersome medical travel programs (Liddy et al., 2017). Certain programs have already been successfully deployed. For example, the TeleLink Mental Health Program supports professional-to-professional education and consultation services for capacity building purposes (Volpe et al., 2014). Considering Ontario and Nunavut’s historical partnership in health, such as Bulletin 2022 for reciprocal billing for out-of-territory health care, further governmental action can be taken to ensure specialty services, routine care, allied health, etc., can be accessed via eHealth or virtual care technology when appropriate (Ontario Ministry of Health, 1999). Amidst the Coronavirus pandemic, the Government of Nunavut has had to make a drastic shift towards eHealth for all variations of health services. Although growing pains can be felt, this experience could lend itself to the future of health practice in the territory. In reflection, the pandemic may present such unexpected benefits as viable models for future health care.

Conclusion

The health of remote Inuit communities lags far behind when compared to the southern Canadian regions. Limited infrastructure, harsh environments, and ongoing operational concerns (i.e. staffing) plague the Nunavut health system, making a complete in-territory health system and challenging endeavor. The Canadian health system needs to devote more resources to the understanding of the disparities faced in this region and adapt to the territorial health care system to better serve this population. The topics presented in the past weeks have demonstrated to me the need to engage this population and Canadian health practitioners in future system development, such as utilizing Inuit health frameworks and prioritizing Inuit health perspectives. This is possible through altering the delivery of care, with the inclusion of unregulated Inuit practitioners and eHealth technology to build capacity within the region to better align Nunavut to create a sustainable and effective territorial health system.

References

Arctic College. (n.d.). Health. Retrieved July 28, 2020, from https://arcticcollege.ca/health

Assembly of First Nations. (2013). First Nations wholistic policy and planning: A transitional discussion document on the social determinants of health. Retrieved from http://health.afn.ca/uploads/files/sdoh_afn.pdf

Clark, B., & Preto, N. (2018, March 19). Exploring the concept of vulnerability in health care. Retrieved from https://www.cmaj.ca/content/190/11/E308

Department of Health. (2016, March). Health Profile Nunavut: Information to 2014. [Report]. Government of Nunavut. Retrieved from https://www.gov.nu.ca/sites/default/files/files/health_profile_nunavut.pdf

Department of Health. (2020, July 24). Health Strategies. Retrieved July 26, 2020, from https://www.gov.nu.ca/health/information/health-strategies-0

Government of Nunavut. (2019, March 01). Call for Proposals – Food Security Initiatives. Retrieved July 28, 2020, from https://www.gov.nu.ca/family-services/news/call-proposals-food-security-initiatives-2

Healey, G. (2017, June 20). What if our health care systems embodied the values of our communities? A reflection from Nunavut. Retrieved from https://www.thearcticinstitute.org/health-care-systems-values-communities-nunavut/

Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami. (2014, September). Conceptual framework of the key social determinants of health for Inuit in Canada. [Image]. Social Determinants of Inuit Health in Canada. Retrieved from https://www.itk.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Overview_FactSheet.pdf

Kral, M. (2016, November). Suicide and Suicide Prevention among Inuit in Canada. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066555/

Liddy, C., McKellips, F., Deri Armstrong, C., Afkham, A., Fraser-Roberts, L., & Keely, E. (2017, June 1). Improving access to specialists in remote communities: a cross-sectional study and cost analysis of the use of eConsult in Nunavut. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/22423982.2017.1323493?scroll=top&needAccess=true

Ontario Ministry of Health. (1999, April 19). Bulletin 2022. Retrieved from http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/ohip/bulletins/2022/bul2022.aspx

Patterson, M., Flinn, S., & Barker, K. (2018). Addressing tuberculosis among Inuit in Canada. Canada communicable disease report = Releve des maladies transmissibles au Canada, 44(3-4), 82–85. https://doi.org/10.14745/ccdr.v44i34a02

[Qikiqtani General Hospital]. (n.d.). [Image] Retrieved August 1, 2020, from https://www.gov.nu.ca/health/information/qikiqtani-general-hospital

Volpe, T., Boydell, K., & Pignatiello, A. (2014, May 14). Mental health services for Nunavut youth: evaluating a telepsychiatry pilot project. Retrieved from https://www.rrh.org.au/journal/article/2673

Comments