PART 2/2: Upstream Currents - An Examination of Youth Nunavummiut Mental Health

- samkriksic

- Jul 6, 2020

- 8 min read

Updated: Jul 25, 2020

This is a follow up to Part 1/2: "The First Nations Wholistic Policy and Planning Model". Part 1/2 in this series is an examination of this health model as it applies to Inuit and Nunavummiut Health. This post (2/2) is an exploration of youth mental health utilizing the First Nations Wholistic Policy and Planning Model.

Introduction

It is widely understood that Inuit Nunavummiut face greater health disparities than their southern neighbors (Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, 2014). Nunavummiut experience considerably higher rates of overcrowded housing, unemployment, food insecurity, substance use, and familial violence when compared to Canada’s southern regions. One can ascertain why Inuit have some of the highest rates of reported mental illness and suicide in Canada, specifically in youth (Gray et al., 2016). This health gap demands action beyond the micro individual level to positively impact the youth Nunavummiut mental health crisis (Department of Health, 2016). The Assembly of First Nations (AFN) Wholistic Policy and Planning Model is one such multilevel, or “upstream”, method of addressing pediatric Inuit mental health and informing future initiatives (AFN, 2013).

Nunavummiut Mental Health

In 2019 the Representative for Children and Youth (Nunavut) published a report called “Our Minds Matter”. This report examines the state of mental wellness and availability of services in Nunavut, stating "the prevalence of mental illness among young people and the strong association between poor mental health and significant health and development concerns is well-established” (“Our Minds Matter”, 2019). The rates of suicide in Nunavut have climbed since the 1970s at alarming rates, specifically among the youth, to the point of “normalization” (“Nunavut Suicide Prevention Strategy”, 2010). “Our Minds Matter” examined data from 1999 to 2017 finding 545 Inuit died by suicide, and that “of those individuals, more than half – 62% - were under the age of 35” (“Our Minds Matter”, 2019). Adapted from Jack Hicks’ “The social determinants of elevated rates of suicide among Inuit youth”, the National Suicide Prevention Strategy published the visual aid below (figure 1) demonstrating the trending rise of suicide in Nunavut versus Canadian national average.

Figure 1

(“National Suicide Prevention Strategy”, 2010)

With the increased availability of data comes an opportunity to more closely examine the contributing factors between the disparity of mental health and suicide rates amongst Canadians writ large and Inuit specifically. The utilization of a multilevel model, such as the Wholistic Policy and Planning Model mentioned above, can assist in identifying gaps/disparities, barriers to development, and will assist in upstream interventions. The National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health defines upstream interventions as “strategies [that] focus on improving fundamental social and economic structures in order to decrease barriers and improve supports that allow people to achieve their full health potential” (Glossary, n.d.). The Wholistic Policy and Planning Model can be used to examine this crisis and inform future upstream action and legislative strategies.

Wholistic Policy and Planning Model

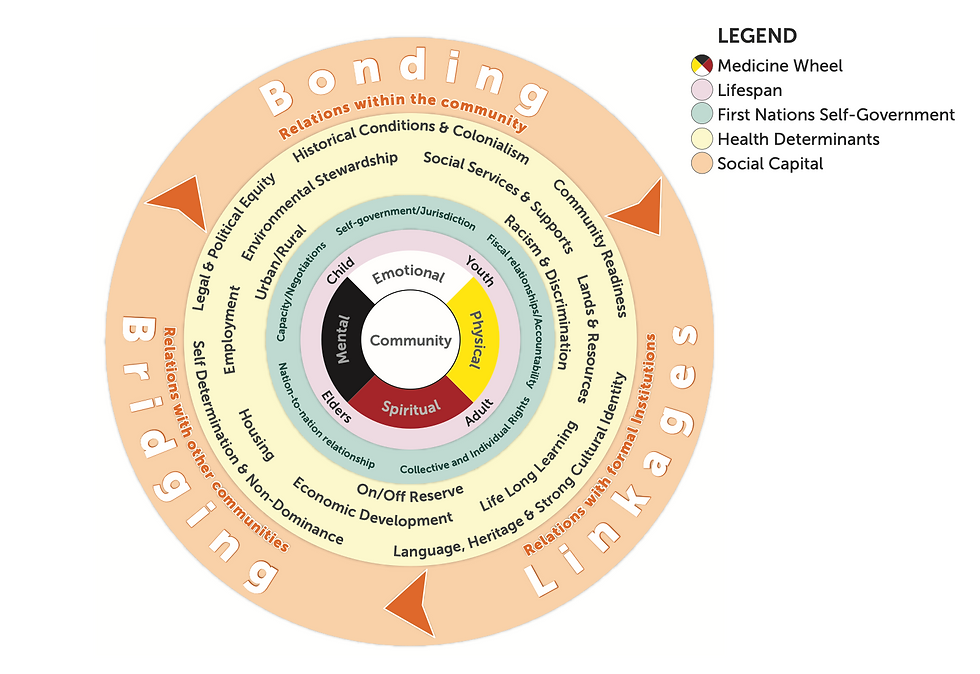

The Assembly of First Nations (AFN) Wholistic Policy and Planning Model is presented as a framework for informed policy development. The model is inclusive of holistic Indigenous ideologies and is structured as a non-linear sphere, where the various relevant dimensions are layered. The framework is displayed below in Figure 2. For an in-depth summary of the model, please refer to Part 1 in this blog series.

Figure 2

(AFN, 2013)

The key components of the model include the community at the core, the medicine wheel, cycles of the lifespan, dimensions of First Nations self-governance, social determinants of health, and components of social capital.

Community at the Core of the Medicine Wheel

Community is at the center of this model, with the components of the traditional medicine wheel (representing the individual) surrounding it. As described in traditional Inuit knowledge, “the Inuit way of being is built on the relationships between these areas of the individuals life and the rest of the human and natural world…in it resides the sense of identity, the collective social supports for the individual, and the sense of belonging grounded in loving, healthy and supportive relationships” (Tagalik, 2012). The sense of community in relation to self is a crucial component of the mental health crisis and the normalization of suicide. In a study published in 2020, the “findings suggest that prior exposure to suicide is associated with increased risk of suicide and suicide attempt” (Hill et al., 2020). If suicide and poor mental health among Inuit youth are normalized, existing trends are likely to continue within families and communities. Approaches to pediatric mental health cannot be limited to the individual but must utilize methods that address the individual within their family and community. An example of an upstream intervention encompassing this ideology is a community initiative to decrease alcohol and substance use. This type of initiative may use strategies such as early intervention and community engagement and will target the wider population.

Four Cycles of the Lifespan

Reading and Wien determined that “health is not only experienced across physical, spiritual, emotional and mental dimensions but is also experienced over the life course” (Reading & Wien, 2009). They establish how determinants can have effects across multiple health stages and “may themselves create conditions (i.e. determinants) that subsequently influence health” (Reading & Wiens, 2009). The importance of the cycles of the lifespan (child, youth, adult, elder) can be seen through intergenerational trauma and its effects on Nunavummiut youth. In an article regarding intergenerational trauma, it theorizes that “suicide behaviours amongst indigenous peoples may be an outcome of mass trauma experienced as a result colonization…the Indian Residential School System set in motion a cycle of trauma, with some survivors reporting subsequent abuse, suicide, and other related behaviours…[and] that the effects of trauma can also be passed inter-generationally” (Elias et al., 2012). The model serves well to demonstrate how an approach to pediatric mental health must be inclusive of interventions across the life spectrum.

Dimensions of First Nations Self-Governance

As per the Canadian Council on Social Determinants of health, this layer further adds to the upstream approach as it prompts consideration for socio-political or intersectoral factors, including historical and ongoing barriers to health (2015). The Nunavut Suicide Prevention Strategy summarized “almost all reasoning around the cause of the elevated suicide rate in Nunavut has to do with the rapid and radical societal change that has occurred here; and most discussions of suicide prevention focus on how to counteract these changes” (2010). This furthers the notion that pediatric mental health must be considered from a broader lens, including the ongoing effects of colonialism and historical trauma, and those future interventions should be developed with cultural specificity, breaking from the westernized models of health care.

Social Determinants of Health

As per the Canadian Council on the Social Determinants of Health, these indicators can be considered “elements upon which upstream action can be taken” (2015). An abundance of data points to lower rates of secondary education, substantial overcrowding and disrepair of housing, consistently high rates of food insecurity, unstable income, and lower employment rates, and disproportionately high rates of risk factors (i.e. alcohol consumption) (Department of Health, 2016). This layer serves to address the barriers and necessary upstream interventions that are required to improve the state of pediatric Inuit mental health. For example, policies and legislation that target unemployment may result in stable households (i.e. food security), thus impacting childhood development for the better and improving mental health outcomes.

Three Components of Social Capital

The final components of social capital (bonding, bridging, and linkage; referring to the relationships within communities, between communities, and with formal institutions) address the requirements for intersectoral collaboration and an Inuit-specific lens for program and policy development (AFN, 2013). For example, Kral notes previous attempts at westernized suicide prevention strategies were generally unsuccessful and suggests culturally appropriate community programs as the key to lowering these rates (2016).

Informing the Future

In response to the Nunavut Suicide Prevention Strategy report, the Government of Nunavut published their action plan for suicide prevention in Nunavut for 2016 – 2017 (“Resiliency Within”, 2016). This report outlines current initiatives that address the suicide and mental health of Nunavummiut youth. The report summarizes eight commitments, which are adapted and summarized below in Figure 3.

Figure 3

(“Resiliency Within”, 2016)

The report discusses indicators of measurement and progress, such as stakeholder reports, employee understanding, number of meetings, attendance in programs, and local engagement summaries. These initiatives are all examples of upstream interventions targeting the downstream concern of pediatric mental health and suicide prevention.

Conclusion

Health inequity has plagued First Nations and Inuit populations in Canada for generations, resulting in a mental health and suicide crisis among Inuit youth. The utilization of a First Nations or Inuit framework to address the needs or disparities within those populations will assist to decolonize the region and recognize the values and inherent priorities of these cultures, with the objective of promoting mental health well-being and lowering the youth suicide rate. The Assembly of First Nations Wholistic Policy and Planning Model is overall adaptable and presents an intersectoral approach that can be utilized to address the systemic issues of youth mental health and suicide. It is well designed to address issues related to colonialism and features important First Nations and Inuit traditional knowledge, making it inclusive while also promoting self-governance. The Government of Nunavut has taken significant steps throughout the last decade to reduce youth suicide and address mental health across the lifespan. Careful evaluation of current programming and ongoing statistics is required to further inform future upstream initiatives.

References

Assembly of First Nations. (2013). First Nations wholistic policy and planning: A transitional discussion document on the social determinants of health. Retrieved from http://health.afn.ca/uploads/files/sdoh_afn.pdf

Canada, Government of Nunavut, Nunavut Suicide Prevention Partnership. (2010, October). Nunavut Suicide Prevention Strategy. Retrieved from https://www.gov.nu.ca/sites/default/files/files/NSPS_final_English_Oct 2010(1).pdf

Canada, Government of Nunavut, Nunavut Suicide Prevention Partnership. (2016, March). Resiliency Within: An action plan for suicide prevention in Nunavut 2016-2017. Retrieved from https://www.gov.nu.ca/sites/default/files/resiliency_within_eng.pdf

Canadian Council on Social Determinants of Health. Social Determinants of Health Framework Task Group, & Canadian Council on Social Determinants of Health. Social Determinants of Health Framework Task Group. (2015). A Review of Frameworks on the Determinants of Health. Ontario, Canada: Canadian Council on Social Determinants of Health. Retrieved from http://ccsdh.ca/images/uploads/Frameworks_Report_English.pdf

Department of Health Nunavut: Chronic Disease. (n.d.). Retrieved July 01, 2020, from https://www.gov.nu.ca/health/information/chronic-disease

Department of Health. (2016, March). Health Profile Nunavut: Information to 2014. [Report]. Government of Nunavut. Retrieved from https://www.gov.nu.ca/sites/default/files/files/health_profile_nunavut.pdf

Elias, B., Mignone, J., Hall, M., Hong, S., Hart, L., & Sareen, J. (2012, March 06). Trauma and suicide behaviour histories among a Canadian indigenous population: An empirical exploration of the potential role of Canada's residential school system. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0277953612001426

Gray, A., Richer, F., & Harper, S. (2016, October 20). Individual- And Community-Level Determinants of Inuit Youth Mental Wellness. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27763839/

Hill, N., Robinson, J., Pirkis, J., Andriessen, K., Krysinska, K., Payne, A., . . . Lampit, A. (2020, March 31). Association of suicidal behavior with exposure to suicide and suicide attempt: A systematic review and multilevel meta-analysis. Retrieved from https://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371%2Fjournal.pmed.1003074

Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami. (2014, September). Comprehensive Report on the Social Determinants of Inuit Health. Retrieved June 11, 2020, from https://www.itk.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/ITK_Social_Determinants_Report.pdf

Kral, M. (2016, November). Suicide and Suicide Prevention among Inuit in Canada. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066555/

National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health. (n.d.).Glossary: Upstream/downstream. Retrieved July 01, 2020, from

Our Minds Matter: A youth-informed review of mental health services for young Nunavummiut[PDF]. (2019, May). Iqaluit: Representative for Children and Youth. Retrieved from https://assembly.nu.ca/sites/default/files/TD-162-5(2)-EN-RCYNU-Our-Minds-Matter-Review.pdf

Reading, C. L., & Wien, F. (2009). Health inequalities and social determinants of Aboriginal peoples’ health. Prince George: National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health. Retrieved from https://www.nccah-ccnsa.ca/docs/social%20determinates/nccah-loppie-wien_report.pdf

Tagalik, S. (2012). Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit: The role of Indigenous knowledge in supporting wellness In Inuit communities in Nunavut. Retrieved from https://www.ccnsa-nccah.ca/docs/health/FS-InuitQaujimajatuqangitWellnessNunavut-Tagalik-EN.pdf

Comments